What does a lender look like… on the inside?

In theory, the mechanics of consumer credit are simple: you borrow a large sum of money at a low interest rate, break it into smaller parcels, and then lend those out with interest rates set high enough to allow the gains made on the repaid loans to cover the losses you made on defaulted ones, plus the admin costs involved in keeping it all together.

In practice, of course, that is easier said than done.

Firstly, you have to acquire that large sum of cheap money, typically from customer deposits, central bank loans, or an injection of public or private capital. Each of these funding sources brings its own set of costs and benefits, none of which I’m qualified to address. Frankly, I know almost nothing about treasury.

So I’ll start this article with the assumption that we have funding in hand. Still, there is a lot to discuss. That parcelling out of loans must be done with risk and competitiveness in mind. Consumers need to be efficiently turned into customers through a sometimes fractious coming together of marketing and originations. Pricing is complicated. And none of this stops when the credit is granted. Customers need to be continuously managed with positive and negative interactions, to optimise the balance between repaid and defaulted loans.

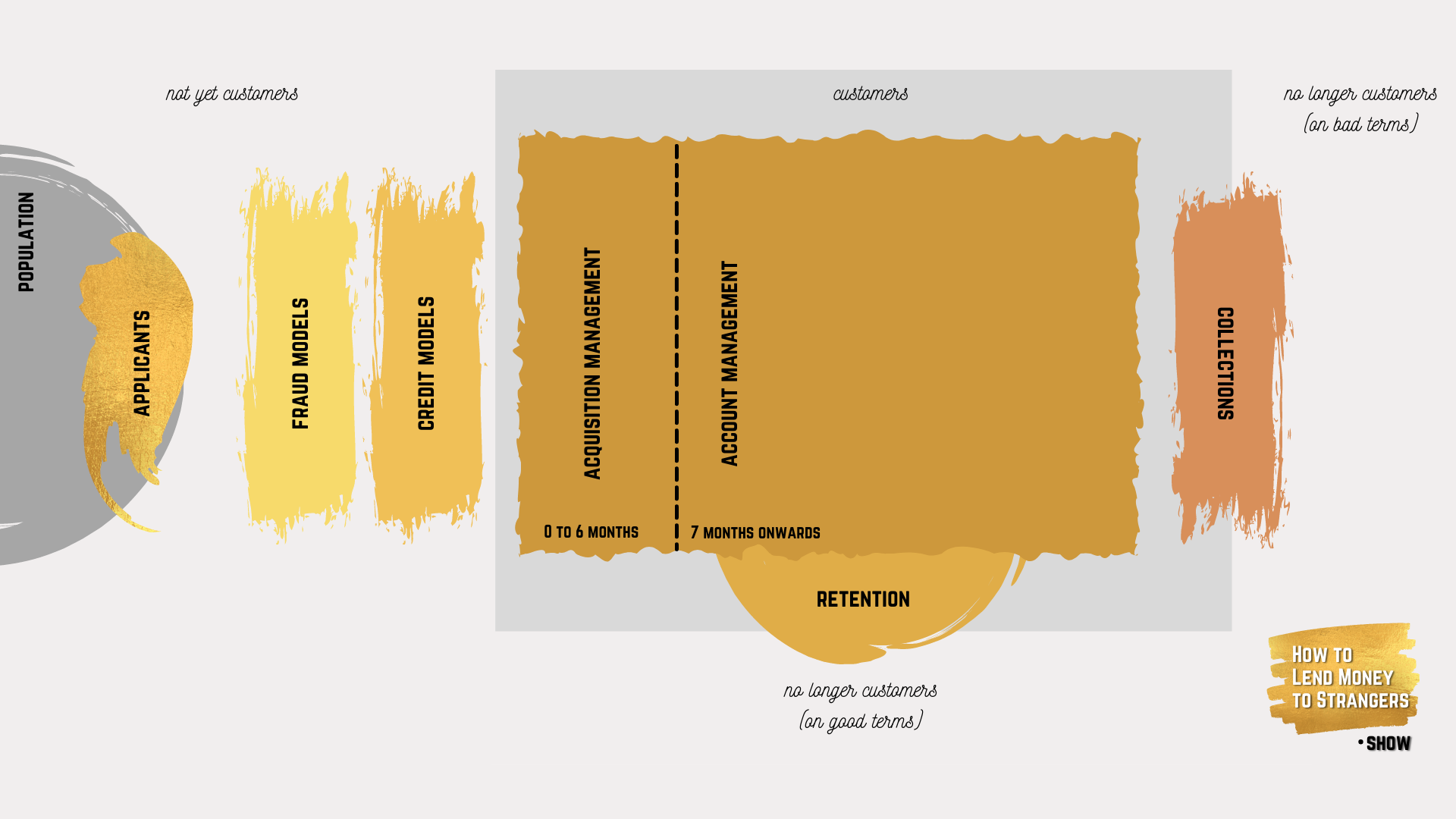

Every lender will address this with different strategies and different organisational designs, but the model below is one that I have used before in my consulting work and which I think does a reasonable job of describing the generic lender. At least that’s all I’m expecting of it here, not to model best practice but to allow me to talk generally about common types of strategic lending decisions.

On the simplest level, we can think of consumers moving through a progression from being not yet customers to being customers to being no longer customers (sometimes on good terms and sometimes not).

This procession will typically be kick-started by a marketing team, whose job it is to identify target customers within the entire population and motivate them to apply for credit. Any applications received are generally passed through some filters before being approved—fraud checks tend to be undertaken by a different team to the one that builds and manages credit risk models. Calling out the fraud function separately, therefore, makes sense, but I’ve also separated credit models from acquisition management and that split might be considered a bit blurrier. I have done this because there is a definite difference in skillsets between the statistically-minded folk who build risk-measurement models and the more business-minded folk who would use risk as an input into their strategies. Thus, in my mind, acquisition management is a customer of the risk modelling team and should be focused on making models more valuable, not on making models more accurate—which could include risk-based pricing, limit assignment strategies, cut-off management, etc.

The initial decision is typically monitored for the first 6 to 12 months by the acquisition team, whereafter a customer will start to qualify for account management strategies—cross-sells, limit increases, etc. Conceivably, a customer could stay in here indefinitely as their mix of products and total exposure ebbed and flowed with their lifestyle demands.

But this too shall pass, as the Persian adage says.

Good customers are always in fashion, and so your competitors will always be trying to win over as large a share of these customers’ balances as possible. Sometimes you can see this coming, sometimes it happens immediately but to truly optimise your lending organisation you’ll need a team looking at customer retention. Not only is it usually cheaper to retain an existing customer than to acquire a new one, even one who may be disappointed with the level of service delivered, but customers who are already within the organisation have far more data attached to them — and that attached data can be used to build more accurate strategies than is the case with a fresh prospect pool.

The other exit point is less desirable for customers, and that’s via the backdoor of collections. Simply missing a payment is usually not enough to break down the customer-lender relationship, and in fact, there’s much to be said for the relationship-building opportunities in early collections, but if a loan cannot be cured internally within a reasonable time it will either be sold to a third-party debt collector or written off—and in either case, the relationship is unlikely ever to recover.

So whenever I am talking about a lending risk strategy, I’ll usually talk about it as falling into one of these functions—marketing, fraud, model building, acquisition management, account management, retention, or collections. I’ll do that for simplicity, but we can never stop thinking about lending risk in its totality because any adjustment we make to one profit lever will have knock-on impacts for all other profit levers down the chain.

The model lays out the key profit levers in a generic credit card business. Marketing can increase response rates by targeting a riskier population where competitor offers may be scarce, but this is likely to increase the reject rate from the scorecards. Or the acquisition team can try to reduce risk and capital costs by decreasing average new limits offered, but this might reduce customer take-up rates. As might higher card fees. Higher risk portfolios might have higher revolve rates, but also higher ratios of accounts in collections and lower recovery rates. Et cetera. Et cetera.

Neither of these models is perfect, and every step shown above can and should be broken down further. That said, I hope it can offer a practical framework around which to structure future articles and podcasts.

In episode two of How to Lend Money to Strangers I discuss this concept with Graham Whitley of Quid Pro Consulting. Graham’s business has been built by attaching real and measurable revenue goals to credit risk strategy changes, and so we leverage his experience in developed and developing markets to discuss both the importance of understanding the interconnectivity of functions as well as the difficulty of making it work in practice!